How companies legally harvest your data — and how to stop them

In 2018 it was discovered that Cambridge Analytica had harvested the data of at least 87 million Facebook users without their knowledge, after obtaining it via a few thousand accounts that had used a quiz app.

Online data collection is insidious and continuous. Today, more data can be collected than ever before: people create as much data every two days as they did from the beginning of time until the year 2000. When looked at on this scale, personal data might seem innocuous.

Companies such as Facebook, Google and Amazon have paid extraordinary amounts in fines and reputational hits to gain access to this sort of valuable data. Data collected by Facebook via the use of programs such Onavo and Facebook Research (which paid teenagers and others for near limitless access to their data) led to the discovery that WhatsApp was used more than twice as often as Messenger, giving Facebook the impetus to purchase WhatsApp in 2014. This proved to be extremely valuable.

In reality, data protection is not something consumers can trust all companies to do. Instead, protecting data requires a proactive approach. This article aims to help you protect your data by making you aware of how your data is vulnerable. We end with some tips on what you can do to help keep your data secure.

Beware dark patterns

Many Onavo users were likely unaware that so much of their data could be accessed, and that this data would be used by Facebook. Onavo required root permissions to users phones, and VPN access to computers, allowing Facebook intimate access to user data. Private messages on social media apps; chats from instant messaging apps (including photos and videos sent in these chats); emails; internet browsing history; and location information were all accessible to Facebook using Onavo.

Of course, in order for apps and websites to legally gain access to this data, they first need to obtain permission from the user. If companies asked for such permission openly and explicitly, users would be more likely to deny these requests. As a result, many companies make use of complex mazes of “dark patterns” to shrewdly and legally gain access to user data.

Dark patterns are used because they garner results. Users are more likely to grant permissions to companies if one or more of the following is true:

a. The user feels there is no other alternative, or that granting permission is the quickest and easiest way forward.

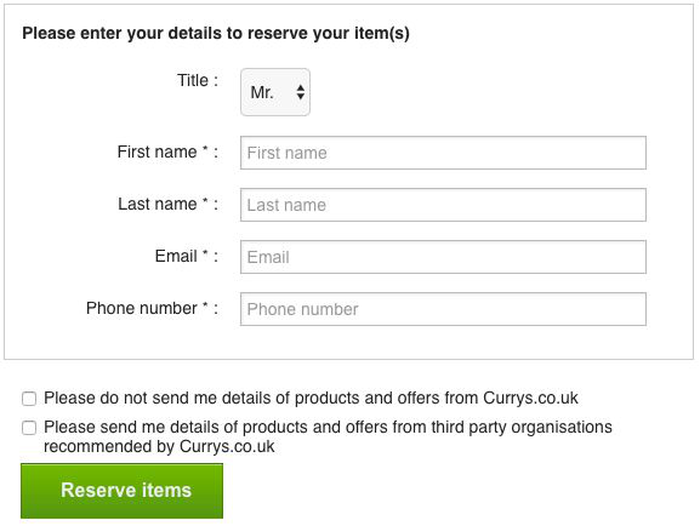

Companies often make it difficult for the user to avoid granting access, by making the steps to deny access during signup unclear and complicated. This “roach motel” method of obtaining permissions can be seen in the infamously complicated path LinkedIn required users to take in order to deny the company access to their contact list.

Removing access that has already been granted is often more complicated than granting access in the first place. Data or cookie tracking permissions settings are not often located in the areas you might expect (such as the “Privacy” section). Misleading wording or unusual actions may also be used to cause confusion. For example, users may be asked to tick a box in order to “opt out” of providing permissions.

b. The user is not aware they are granting access

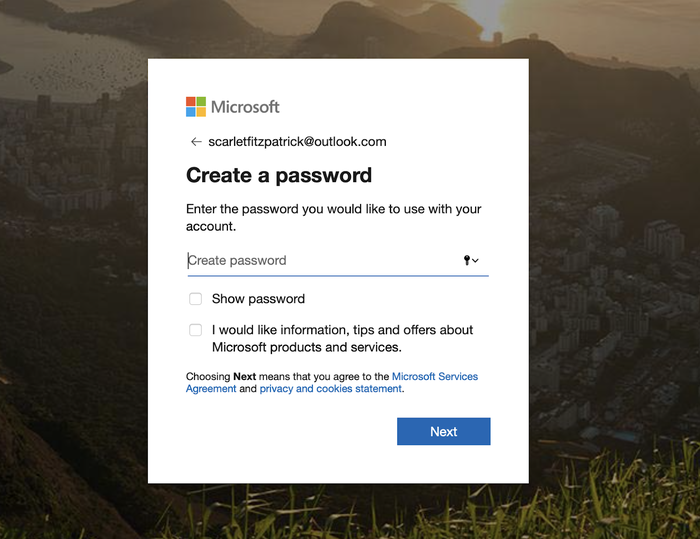

Granting permissions is often tacked onto another, more evident step, such as creating a password. Employing this method may make users less likely to identify that they have agreed to certain data permissions. The use of small print also increases the likelihood that such agreements may be overlooked.

c. The user feels pressured to act quickly

This is usually achieved by one of three pressure tactics:

- Creating a sense of scarcity. Booking.com often falsely claims to have just "1 room left" in order to tempt you to book your stay quickly.

- Introducing time pressure. We’re familiar with this tactic when purchasing certain items, such as flights and tickets: booking companies place a time limit on items in your cart. Companies can use similar tactics to gain permission from your data, too. Facebook appeared to use fake red notification dots which appeared when users were prompted to agree to new privacy agreements, perhaps to tempt the user to hastily agree in order to read their messages.

- Resorting to scare tactics. Here are the terms Facebook used when asking for access to face recognition data: “If you keep face recognition turned off, we won't be able to use this technology if a stranger uses your photo to impersonate you.” Unfortunately, scare tactics are ubiquitous in data collection, as the distinction between those accessing data in order to protect it, those who intend to to absorb it is blurred.

Perversely, 3 of Jakob Nielson’s 10 Usability Heuristics, created to promote user understanding of online systems are often subverted by dark patterns designed to promote confusion and rash decisions, and this, coupled with guiding colours and layouts which suggest the correct items to click (highlighted sections, green buttons), make it more likely for users to follow a predetermined path laid out by those who want access to personal data.

Even when laws are indisputably broken, the punishment is often not significant enough to act as a serious deterrent. Large tech companies found to be in violation of laws are typically punished by fines, such as the $170 million Google paid in late 2019 after it was found that YouTube had violated the 1998 Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA). While this is undoubtedly a large sum, it barely scratches the surface of the company’s profits, calling into question the effectiveness of such penalties for colossal tech companies.

Encryption is not infallible

If you use an iPhone — and don’t play around with your settings — much of your data is already encrypted. Great! Encryption means unhackable, right? Well, sort of. Theoretically powerful computers in the future will be able to decrypt encrypted data, though that’s likely hundreds of years away (and they would need to have access to the encrypted data).

Just because your data is encrypted doesn’t mean it’s always safe. Consider, for example, different approaches to encryption. “End-to-end” encryption is the gold standard, as it means that data is encrypted at both ends of communication, and also in transit. However many services only encrypt data in some situations, and not necessarily whilst it’s at the company’s end or “at rest” on your device.

In fact, lots of personal data isn’t fully encrypted at all times. Your browser might tell you a connection to a site or service is secure, but that doesn’t mean the underlying service is secure. Gmail and Evernote are examples of product that use encryption, but don’t aren’t end-to-end encrypted, which is what enabled a Googler to read user messages. (It’s worth noting Google has put a lot of safeguards in place since then, but the practice still occurs.)

In some cases, companies may pass data that you believe is fully encrypted on to other companies. If you use a third-party email app, they may have access to your data, too. Google allows third party apps to access your email data, meaning any third party app with full access to your data can legally read your emails, too, without specifically requesting access from you.

Recordings from smart speakers — such as Amazon’s Alexa— are encrypted during transit, but aren’t effectively encrypted when they reach Amazon’s cloud, allowing one customer to be sent 1,700 audio files obtained from another user’s Alexa.

Safeguarding encryption keys

It's possible to encrypt data in a way that makes it fully secure. If a company stores data that’s encrypted with a key that only the end-user has access to, then the company and anyone else who doesn’t have the key will have no way to decrypt the data. If there’s no way to access such data, all of the things that would otherwise require safeguards go away: the company can’t get bought and change its policy, it can’t slip up and leak data, and it can’t share data.

iCloud backups of iPhones and iPads — widely assumed to be well-protected — are not completely inaccessible to others, as Apple retains a key to decrypt them This was a conscious decision made by Apple, likely made in order to prevent customers being permanently locked out of their data (we explore those trade-offs here), or made as a result of pressure from the FBI.

Whilst iCloud backups are vulnerable, other sensitive data such as Health, iCloud keychain and passwords are fully end-to-end encrypted with a key that Apple doesn’t hold, so this information can't be accessed remotely. Whilst this doesn’t apply to all data Apple stores, end-to-end security without central key storage is this is one of Apple’s unique selling points.

Apple provides a framework named “CloudKit” for app developers to build on, and data stored in CloudKit is end-to-end encrypted. One example of a developer putting this to good use is Bear, a note-taking app. As Bear uses Apple’s technology for data storage, even the programmers at Bear themselves can’t access your data, and neither can Apple. Only the data owner can.

Building systems like this requires caution, and it’s easy for innocuous mistakes to undermine the effectiveness of encryption. Apple’s “Messages in iCloud” service suffers from this: Apple don’t explicitly hold the key to this data, but a copy of the key can be included in a user’s iCloud backup, and Apple holds the keys to them. Thus one service can provide the key to unlock another.

Not all apps on Google Play are safe

Apps available on Apple’s App Store tend to be secure, as Apple reviews them painstakingly before they’re authorised for download. This is often seen as a deterrent for app developers, as getting an app on the App Store can be significantly more time consuming and costly than getting an app on Google Play. The reason for this is Google Play has a much less stringent app review process. This may be good for developers, but it’s bad for consumers, as it makes it more likely that unsafe — and even malicious — apps will find their way onto the Google Play Store. When the scale of data mining from Facebook Research and Onavo came to light, Apple immediately pulled the app from their App Store, whilst Onavo continued to be available via Google Play weeks later, until it was eventually removed by Facebook.

In April 2018, a report by Sophos Labs looked at 200 apps on Google Play, and concluded that over 50% of all free antivirus apps available on the service could be classified as “rogueware”. The report noted that some apps had been downloaded to 300-400 million times, and warned Android users against downloading free antivirus apps from the Google Play store.

While the primary aim of most of these malicious apps was to lead users to believe that they had viruses that would require payment to remove (some apps appeared to download a virus, validating their claim), many also requested access to a number of sensitive data permissions. The permissions requested by such apps were often beyond the scope of functions a typical antivirus app would need, such as location access, camera access and accessing the user's phone without their knowledge.

Since the Sophos Labs report was published, Google has made efforts towards securing their app store. In November 2019, the company put together the App Defense Alliance with three antivirus firms — ESET, Lookout, and Zimperium — in an effort to eliminate the presence of malicious apps from the Google Play store. It’s unclear, however, that the App Defense Alliance will also be concerned with protecting user data.

Antivirus software doesn’t always offer protection

The use of third party antivirus software has reduced over the past decade due to three factors:

- Users are increasingly storing their data on the cloud, usually in an encrypted state, rather than locally on computers that might otherwise benefit from antivirus software.

- Proportionally more data is on smartphones, which tend to have tighter built-in controls and regulations surrounding safety than computers.

- Modern operating systems include antivirus protection as standard (such as Mac’s Gatekeeper, or Microsoft’s Defender).

The declining use of third party antivirus software has left these companies in a tricky situation, leading to antivirus mergers and efforts to pivot into other spheres in order to stay afloat. As antivirus software is generally granted extensive access to data stored on computers (a necessary step if the software is to identify malware stored anywhere on the computer), these companies are granted access to a lot of sensitive data. Antivirus software has been successfully used as a tool for back-door spying due to its considerable access to data.

Almost all of the antivirus companies advertised today are based in countries with weak data protection laws, or using shell companies to appear to be otherwise. Not in Europe or the US? No Data Protection Act (British), no GDPR (Europe), and no SafeHarbor (US). That makes it easy for these companies to find additional methods of capturing value from user data.

The location of these companies benefits their transition to offering VPNs alongside their typical antivirus software. VPNs funnel all of a user’s data through a third party. This can be sensible, in that it shifts a user’s internet traffic into a path that may avoid some authorities, but it puts that data in the hands of private, unknown companies. A large number of popular VPNs are either based in China or have Chinese ownership, which, considering that VPNs are officially banned in China, may indicate that there are good questions to be asked about the security of this data.

VPNs are aggressive in their advertising and marketing, increasingly using YouTubers for paid advertising, and Google is drowning in sites earning affiliate fees for promoting VPNs, to the extent that it’s almost impossible to find authentic reviews or editorial. This seems unlikely to change. If you were a new entrant, and you wanted to build an excellent product and operate it ethically, you wouldn’t go into competition against desperate offshore AV companies! It's ironic that the majority of companies left in what should be a high-trust market are highly suspect.

With these thoughts in mind, there are a few principles and steps one can take to safeguard data, and they're outlined in the section below.

How to protect your data

Here’s a brief list of steps you can implement to safeguard your data. If you’re an iPhone user, check out our deep-dive into protecting your iPhone, photos, & iCloud account.

- If you must use Android, use a phone made by Google (such as the Pixel), as Google is the only vendor that reliably provides regular software and security updates. Beware of the risk involved in downloading apps from Google Play. If this seems restrictive or onerous, consider switching to an iPhone.

- Be careful downloading apps, or signing up for services. Beware of dark patterns, and services run by anonymous companies, or companies outside of territories with strong data protection laws (Europe, US, Canada).

- Don’t rely on ad-based services like Facebook — at worst, don’t login with Facebook or install the app — or products like Google Wi-Fi which remotely collect data. Powerful firewalls like Little Snitch (macOS) or Guardian Firewall (iOS, “To us, data is a liability, not an asset”) can block or highlight invasive data collection.

- When finding apps or software, don’t rely on reviews other than those found in the App Store or trusted 3rd-party review sources. It’s easy to fake reviews on a website, to create small fake independent review sites, and to show star ratings in Google Search results. Even larger review sites like Trustpilot can be manipulated, but they’re still likely the best source of reviews.

- Be aware of your webcam and mic: apps that use them won’t necessarily make it clear. Even Mark Zuckerberg keeps his blocked when he’s not using it. Consider a webcam shield and mic block which can prevent your computer from being able to record you.

- Use two-factor authentication (2FA), but don’t use it over SMS. It’s relatively easy to carry out what’s known as a “SIM-jacking” attack to gain access to another person’s SMS messages. Twitter's CEO was successfully attacked this way in 2019.

- Take regular backups of your iPhone or iPad using iTunes or iPhone Backup Extractor (both free for this functionality) rather than using iCloud, as iCloud isn’t end-to-end encrypted and has a free storage limit of 5GB.

- Use full-disk encryption (FDE). Modern iOS and Android devices have this enabled by default, but your PC or Mac won’t. On the Mac, this is called FileVault, and on Windows it’s called BitLocker. Without FDE, it would be easy for anyone to simply remove the hard-drive from your computer to see your data, bypassing whatever password you use to secure your account.

- Don’t defer software updates. Whilst it can be frustrating when it seems like your computer, phone or browser wants to update and restart often, these updates often contain vital security updates.

- Password management apps can be invaluable in helping users set and remember distinct, secure passwords for the apps and services they use. Good password managers can also detect duplicate or weak passwords, and check yours against databases of leaked passwords, such as haveibeenpwned. 1Password and LastPass work well.